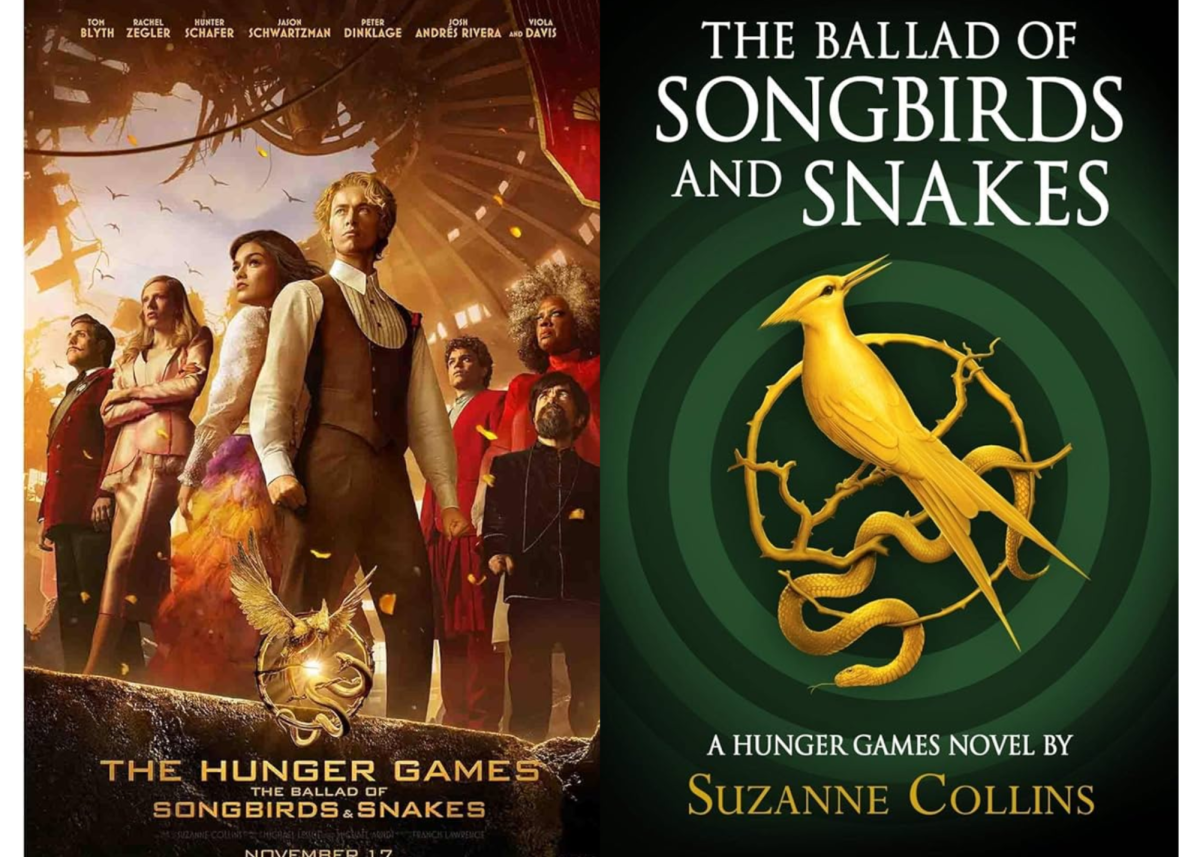

The character of the fleshed-out, sickeningly relatable antagonist is indubitably fascinating, as evidenced by the myriad of media exploring villains such as Cruella de Vil, Anakin Skywalker and the Joker. The newest installment to the Hunger Games universe, The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes, first released as a novel on May 19, 2020 and later as a movie on Nov. 17, 2023, utilizes this narrative. It tells the tale of the despicably cruel President Coriolanus Snow, giving context to the root of the villainy he enacts in the original trilogy. A compelling story set in familiar locations to Hunger Games fans, it further delves into the world of Panem and the themes of cruelty, chaos and control that are introduced in the original trilogy from a fresh angle.

The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes is set 64 years before the original trilogy. The story spans three parts: from right before the reaping for the Games, to the Games themselves to the aftermath of it all. Coriolanus Snow, played by Tom Blyth, is but 18 years old, and the Hunger Games have only just reached their tenth anniversary. The end of the war that inspired the beginning of the Hunger Games had, of course, ended a mere decade before, and the echoes of it still cling to the lives of those living in Panem. A dwindling interest in the Games leads star students at the Academy—Coriolanus and his classmates—to be assigned as mentors to that year’s tributes in an attempt to revive interest.

Coriolanus is assigned the girl from District 12, Lucy Gray Baird, portrayed by Rachel Zegler. Despite his initial misgivings, Lucy Gray’s spunk, sass and sincerity lead Coriolanus to care for her, to truly want her to win. However, he has his own reasons for wanting to take the title of victor alongside Lucy Gray. Coriolanus’s family fortune was decimated in the war and his family home is at risk, not to mention he is unable to pay for university. Winning the Games is his way out. The story revolves around Coriolanus and Lucy Gray’s relationship and the friction between their mutual attraction and the allure of their personal desires; it is the centerpiece of the plot and the driving force behind many of their actions.

The story itself is entertaining, a thought-provoking foray into the already-established Hunger Games universe, drawing on familiar themes, locations and characters in an original way. It’s a welcome deviation from the original books without fully departing from them. The plot is plausible and pleasing, if a bit abrupt at times, and the characters are either painfully relatable or deliciously corrupt.

One of the most enticing aspects of the book is how the Capitol is in disarray, even a decade after the war. Coriolanus spends the first two parts of the novel desperately keeping up appearances to maintain his public image, a direct but subtly integrated parallel to the city he resides in. Though the streets are cleaner than they used to be, there are still crumbled buildings and visible piles of debris. The Games are messy, disorganized and chaotic, completely departed from how they are decades later, when Katniss Everdeen arrives in the arena. Tributes are constantly on the verge of escape, violence is always in threat of breaking out and the Games are poorly broadcasted. However, the movie completely disregards this. The Capitol is portrayed as just as polished as ever, streets clean and full of cars. Cranes rebuilding skyscrapers in wide shots are the only hint of discomposure. The role of the students in running the Games is significantly downplayed, and there’s not ever a doubt in engagement. In the arena, there are cameras installed in every nook and cranny. The choice to ignore the Capitol’s weakness undermines a major theme of the story—the struggle to hold onto control.

Of course, with any story that focuses on moral degradation, character development is an absolutely integral element of the plot. It builds a sense of sympathy as well as gives reasoning for characters’ later decisions. In the novel, which is entirely from Coriolanus’s point of view, the reader is privy to his inner dialogue and logic as he navigates the treachery of the Capitol and the complexities of his day-to-day life. The necessity of this train of thought is taken for granted until one watches the movie, and Coriolanus’s character development goes out the window.

In addition to the loss of his internal dialogue, Coriolanus’s initial sympathies and kindnesses are written out of his character in the movie. All the other characters—save, perhaps, Dr. Gaul—lose much of their depth as well, making it so a viewer who has never read the book would think Coriolanus was always a little bit evil, Sejanus Plinth is confusingly self-righteous and Lucy Gray is just a quirky girl from District 12. With this loss of profundity, characters lose vital aspects of their identities, becoming akin to beautifully embellished paper dolls. An unfortunate but inevitable side effect of this is shallow, stunted relationships that feel as though they exist for the sole purpose of propelling the plot.

The efforts made to expand the story were poorly chosen. Instead of focusing on character development, as the book does, the movie hones in on action sequences, many of which don’t even occur in the book. In the movie, the Games are made out to be exciting, spectacular and violent, beginning with Lucy Gray getting chased by a horde of tributes after epically escaping the fray in the center of the arena. In the book, the Games are pitiful, slow, wretched and stilted, a choice that highlights their morbid ridiculousness. The decision to add more action to the plot limits the story rather than broadens it, taking up screen time that could have been used to more sufficiently explore the characters.

Stylistically, the movie is excellent. It visually interprets the tone of the book quite expertly while holding true to the Hunger Games look that fans will recognize from the original movies. The costume design is particularly well done. The fashion is reminiscent of 1950s American fashion—which, of course, was also a decade directly after a devastating war—with a dystopian twist. It is nowhere near as ridiculous and opulent as the fashion that beguiles Capitol in later years, but the potential for such is peeking out from between the seams.

Music plays a significant role in the story, and the movie’s soundtrack does not disappoint. Although Lucy Gray sings much more in the novel, the songs and musical scenes that were chosen to appear in the movie were well-selected. Other than Lucy Gray’s alternatively raucous and emotional performances, the soundtrack isn’t particularly unique, but it serves its purpose well.

With what they were given, the actors performed well. Blyth’s Coriolanus was a believable interpretation of the character that, although not as well-rounded as his book counterpart, satisfactorily portrayed the future President Snow. Zegler perfectly captured the spirit of Lucy Gray, with her unwavering confidence and lively yet solemn demeanor. Though Sejanus was written extremely underwhelmingly, Josh Andres Rivera ran with what he had and delivered a portrayal that, considering his limitations, lined up well with the character in the novel. Any shortcomings in the characters were entirely attributable to the writing rather than the acting.

Production began on the movie before the book was even released, with the two projects developing side-by-side. With that in mind, it is especially intriguing how the movie managed to fall short on certain key aspects of the book—particularly, character development and the implementation of many of the overarching themes.

The movie adaptation of The Ballad of Songbirds of Snakes is best enjoyed after reading the book due to its watered-down nature, an unfortunate shortcoming that will leave the average movie-goer unaware of the actual breadth of the narrative. However, both the movie and the book are an undeniably engaging expansion of the Hunger Games world. The book is available to purchase on Amazon or other booksellers, and the movie is available to buy on Prime and Apple TV.