A peek into the birth of a rock legend, 61 years later

If Bob Dylan is known for anything, it’s his classic rock sound. Ask any fan of rock music to name songs from his extensive discography, and one will no doubt hear “Like a Rolling Stone,” “Subterranean Homesick Blues,” and “Mr. Tambourine Man,” among others. However, some earlier Dylan songs, like “The Times They Are A’Changing” and “Blowin’ in the Wind,” are his most popular and prime examples of early folk Dylan trumping his later rock iteration.

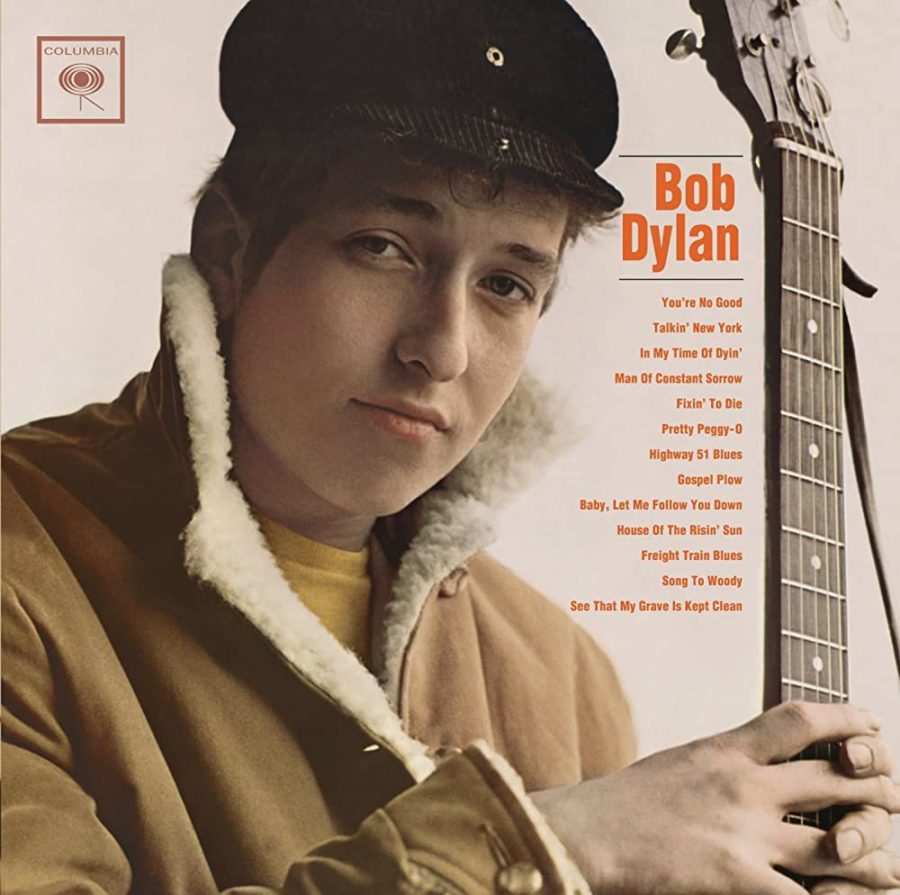

The albums that claim these early hits seem all around less appreciated. While it’s a shame, it’s not hard to understand why; which is more iconic–the no-nonsense, leather-jacket clad Dylan of Highway 61 Revisited, or the indistinct, unemotive Dylan of his 1962 self-titled album, Bob Dylan? Later-era Dylan feels more fashionable and rock’n’roll, thus making it more accessible.

Despite not having the mainstream appeal of Dylan’s later records, there is a lot of unappreciated beauty and folk rawness in Bob Dylan, which celebrated its 61st anniversary on Mar. 19. This album is not only an insightful peek into the early mind of a rock legend, but also arguably one of Dylan’s best works ever.

The album starts off strong with “You’re No Good.” As with many songs off the album, it’s a cover, this one from bluesman Jesse Fuller. Despite it being an unoriginal work, Dylan proves immediately–and repeatedly throughout the record–that he knows what will make a good cover. He effortlessly adapted “You’re No Good” into his signature folk style, merging together all of his most iconic qualities. His voice is creaky and strained, raw as he tells a story about love gone wrong against a frantic and jangly guitar track. “You’re No Good” is the opening act for Dylan’s career, and as the track plays on, the listener can almost see Dylan perched on stage, the crowd entranced as he sings the lyrics, “You give me the blues, I guess you’re satisfied/You give me the blues, I wanna lay down and die.”

The next song, “Talkin’ New York,” opens with a slow harmonica melody and lazy, bumbling guitar. Dylan speaks softly and sweetly over the instrumentals in one of the album’s two original songs. Through spoken word, Dylan is able to create a strong understanding of himself as an artist and a person, as though he’s sitting down at a coffee shop on a cold Minnesota morning and shaking hands with the listener. He rambles, remarks, and jokes all while leaving room for comedic pauses with lyrics like, “Wintertime in New York town/The wind blowing snow around/Walk around with nowhere to go/Somebody could freeze right to the bone/I froze right to the bone.”

The song more deeply speaks about the experience of chasing the American dream, only to find out it’s not as fair or easy as some make it seem, “Now, a very great man once said/That some people rob you with a fountain pen/It don’t take too long to find out/Just what he was talking about.” The song wraps up with a “so-long” to New York from Dylan while a cool, comforting feeling washes over the listener, as though he waved goodbye to them as he stood up from the coffee shop table and left, a breeze washing in from the doorway and fading against the radiant warmth of inside. Dylan’s record offers a break from the rat-race of daily life, as reuniting with a friend who left long ago feels.

Contrasting the overall jolly feel of the record is Dylan’s cover of “House of the Rising Sun,” a truly ghastly and haunting track. The song is listed near the end of the album and tells the story of a woman trapped in a drab, dead-end life returning to her childhood house as her life comes to a close. Dylan’s performance here proves that he can be a thoughtful and heartsick musician just as well as he can a charismatic folk singer. His voice falters throughout, reaching a peak near the end as he howls loudly, hurling out feelings of mediocrity and struggle through clenched teeth. Such a performance could not have been without his charmingly rough and amateur voice. The words, “I’m going back to New Orleans, my race is almost run/I’m going back to end my life down in the rising sun,” will ring out in the mind of listeners long after the song ends.

Immediately after such an emotional song is the far more light-hearted “Freight Train Blues.” Here, Dylan does what he does best: has fun and pushes boundaries. The instrumentals on this track are fast-paced and energetic, a sonic train flying through open fields, chugging toward the next town. The harmonica is the up-beat kind that one could picture old-time cowboys dancing to in a desert saloon, all rough yet deliberate in each soaring puff of sound. Dylan experiments with a falsetto throughout, at one point holding the same note at an impressively high pitch for about 15 seconds. This small part of the song is out of place and maybe a little off-putting at first, and it may leave listeners wondering, “Why?” The answer is simple. He did it because he could, and that’s what he does. Dylan is a master of injecting himself into his music, especially the early stuff, with strange technique that is less traditionally musical, and more along the lines of a friend asking another, “Want to hear how long I can blow the same note on this harmonica for?”

Ultimately, Bob Dylan is a sweet glance at the younger, more amateur side of a musician that would go on to become the well-loved, rocking Dylan that so many treasure. After its 61st anniversary, it is definitely worth going back and listening to.

Lincoln Wheeler (he/him) is a senior who loves playing hockey and guitar. He enjoys being a journalist because he wants to bring new perspectives and ideas to people.

Glenda Jenson Wheeler • Sep 15, 2023 at 7:24 pm

A beautifully written and thoughtful review. Bravo!