Outdoor school inspires, tires student leaders

One week. One cabin. Twelve sixth graders. Outdoor school is a program in Oregon that allows over 7,000 sixth graders to escape into the woods each year for about six days of hands-on science learning.

A key aspect of the program is that high school student leaders volunteer to be cabin leaders and field study instructors for the week, giving them the opportunity to develop leadership skills and relive their own sixth-grade experiences.

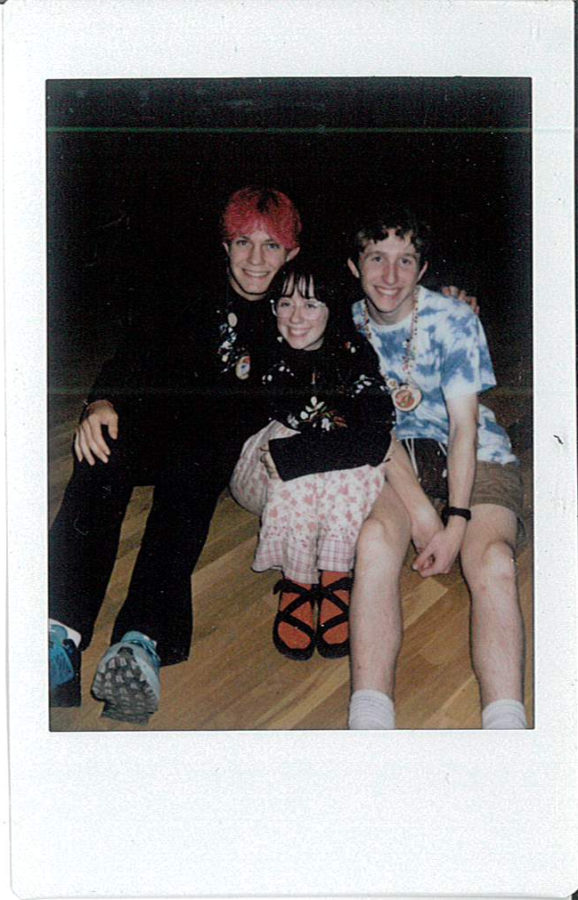

While I participated as a student leader in the spring of 2022, this fall outdoor school session was the first to be fully overnight since the beginning of the pandemic. As a result of COVID-19 precautions last session, sixth-graders only came during the day. The return of the overnight program meant new struggles, joys and connections.

Student leaders arrive on Sunday afternoon in a bus filled with high school students from across the metropolitan area, with schools such as West Linn, Grant, McDaniel and St. Mary’s represented. This week, I was at Camp Namanu, about an hour outside of Portland, right along the Sandy River.

The most important thing to know about outdoor school is that if you do it right, you will undoubtedly lose your voice. Whether it’s from belting “Siegfried the Slug” or screaming “Don’t eat that mushroom!” on the trail, you should be prepared for many nights with a hot cup of tea and honey to recover your voice.

Junior Miles Greene (known as Green Bean at outdoor school), a first-time counselor at the Kuratli site, lost his voice by day three of outdoor school.

“Most of the kids were really nice, but there was a lot of yelling involved,” Greene said. “There was a lot of telling kids to keep their hands to themselves, a lot more than I expected.”

My voice started to disappear after a few passionate renditions of “Rattlin’ Bog”. The electrifying energy of the nightly campfire encourages commitment to the classic repeat-after-me songs at full volume. Every student leader gets the chance to lead a few songs, and it’s definitely worth the vocal cord impairment.

Sleeping in a cabin with 12 middle school boys is, indeed, as chaotic as it sounds. The first night was the most difficult—I had known them for a total of five hours and they had no interest in listening to some random high school kid about what time they should be in bed. After an hour or so of pleading with them to settle down in their bunks, I was able to fall asleep at 10:30.

Until, surprise! About 20 minutes past midnight, I was awakened by the boisterous laughter that could only stem from lewd jokes and conversation. Bleary-eyed, I walked to where the noise was and sternly let them know that if I was awakened again, we would have some problems. This conversation was repeated multiple times throughout the week, but for the most part, I was able to get at least six hours of sleep.

Even more enjoyable than getting them to bed is waking them up. I gently tapped them awake at 7:00 and herded them to breakfast, with varying success.

Days at outdoor school run from about 6:45 a.m. to 11 p.m. for student leaders, sometimes longer. While there is an ever-present well of coffee in the dining hall, there is only so much caffeine can do for you after 16 hours of sixth graders.

Senior Cecilia Mouton (known as Lime at outdoor school) also attended week 2 of outdoor school at Camp Namanu. This was her second year volunteering at outdoor school, but there were still some challenges.

“The hardest part of outdoor school was making sure every kid is having a good time, and safe and engaged,” Mouton said.

That was also the most rewarding part.

“I have fun when the kids are just interested in what we’re doing,” Mouton explained. “They’re excited about the community and they’re interested in me and the other student counselors.”

Outside of the cabin and meals, the days are structured around field studies. Monday through Thursday, students cycle through plants, soil, water and animal field studies, where they get the chance to go on hikes, search through the water, and do stations to help them learn more about the scientific process.

These were often the most difficult and fatiguing parts of the day; sixth graders would get bored of the hikes or lose interest in fungi. However, when they were engaged and interested, it was lovely to have discussions about the role of different organisms in an ecosystem or debate why fire was necessary in nature.

I think part of the joy of outdoor school comes from the shared exhaustion that everybody faces. As the week goes on, you grow a strong bond with other student leaders and staff as you all witness the terrors and joy of sixth graders gone wild. You watch them mash biscuits and gravy with chocolate milk and spread it on the table at breakfast, but then during field study, they sing a fungi parody of “Shake It Off” and you remember why you’re at outdoor school.

Additionally, being able to make an impact on these sixth graders’ lives and play a role in their development is really powerful. Many sixth graders remember their outdoor school counselors for years and are transformed by their experience.

Luke Belt is a junior at Roosevelt and was a second-time student counselor at Camp Namanu. He saw firsthand how influential student leaders are as role models.

“There was this one kid in particular I had who was fairly distractible and didn’t pay the best attention,” Belt said, “but took the most notes during field study and wrote in his thank you note how he learned a lot from my teaching.”

There is no doubt a significant impact on students. Learning in a new environment with different, younger teachers is an exciting experience, but it’s also impactful for student leaders.

“Everything you do is outdoorsy, the community is the most accepting you’ll ever meet, the kids are a surprising ego boost, and everything in between makes Outdoor School feel like the perfect vacation. It’s made my overall mood so much better throughout this year.”

The connections I built with the students were definitely the most fulfilling for me. Even the most difficult and uncontrollable children had moments of vulnerability and compassion where they expressed their appreciation for outdoor school and the student leaders.

As the end of the week grew closer, emotions intensified. Late-night cry sessions were a staple as we reflected on the time we’d spent together and realized it would soon be over. As we sang the buses goodbye, I was grateful to not have to deal with any more sixth graders but sad to know I would likely never see any of them again.

My woes were quickly interrupted by a few hours of frantic cabin cleaning and prep for the next week, and before I knew it, we were loading onto the bus home. Just over 120 hours away from school, technology and normal life, and now we were returning to loads of homework and catching up.

Being a student leader isn’t an easy task, but it’s one that allows for an escape from the monotony of daily life. Building relationships with sixth graders and seeing the joy on their faces as they begin to learn and understand science is an unparalleled experience and is worth the sleepless nights and catching up on homework.

Lane is a senior, and he is passionate about wrestling, transit access and oxford commas. People describe him as intense, driven and hungry. He likes being a journalist because he can shed light on controversial issues and bring the voices of marginalized communities into the spotlight.